Law Of The Land: Constitutional Documents

LAW OF THE LAND: CONSTITUTIONAL DOCUMENTS

Grace Ho 3 Years Ago 13 Min. Read

Law of the Land: Highlights of Singapore’s Constitutional Documents is an exhibition on Singapore’s constitutional history – from its founding in 1819 to independence in 1965 – organised by the National Archives of Singapore and National Library Board, and hosted at the National Gallery Singapore. Kevin Khoo, an archivist from the National Archives and one of the exhibition’s curators details some of its highlights. This essay was originally published in the National Library Board’s BiblioAsia magazine, Jul-Sept 2016 issue.

To raise awareness of how legal history illuminates many milestones in the story of our island-nation, a new exhibition, Law of the Land: Highlights of Singapore’s Constitutional Documents, opens on 19 October 2016 at the former Chief Justice’s Chamber and Office at the National Gallery Singapore. Organised by the National Archives of Singapore (NAS), the permanent exhibition explores the history of Singapore’s constitutional development from its founding as a British settlement in 1819 to its emergence as a sovereign republic in 1965. The exhibition features rare documents from the collections of both the NAS and the National Library that capture key moments in Singapore’s constitutional history. The Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (the Constitution) is the supreme law of the land that all other Singapore laws conform to. It prescribes the important distribution of authority between the three arms of the state; the legislature, the executive and the judiciary. The Constitution also safeguards fundamental rights Singaporeans enjoy, such as equality before the law, equal protection of the law and the freedom of religion, among others. The Constitution has been called a “pragmatic document” that provides the framework for social, political and economic development to help Singapore thrive.[1]

A NEW LEGAL SYSTEM

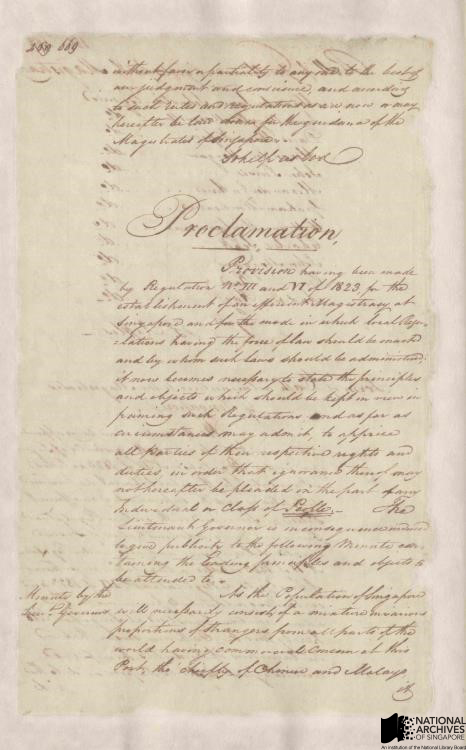

The beginnings of Singapore’s modern constitutional development is tied to the arrival of Stamford Raffles in 1819.[2] One of the first things that Raffles did was to promulgate a series of six regulations that were eventually published in 1823.

The legal ideas in this nascent set of laws were based on English law, adapted to accommodate the customs of Singapore’s indigenous and migrant communities. Unfortunately, these regulations were essentially illegal, as Raffles did not have the authority to enact laws and intended his regulations to be provisional until a formally authorised legal code was established.

These provisional regulations were in force at least up to 1826[3] – the year Singapore became part of the Straits Settlements together with Malacca and Penang – and although they provided for a basic legal system applicable to all in the Singapore settlement, in practice most disputes for non-Europeans were handled by indigenous chiefs who settled cases according to local customs and social mores. Europeans came under the direct jurisdiction of the British Resident’s Court.

Raffles’ regulations reaffirmed Singapore’s position as a free port and created a basic set of laws for matters such as registering the transfer of land and prohibiting slavery and gambling. He also provided for the appointment of magistrates to hear civil and criminal cases. Raffles penned an accompanying ‘Minute’ in 1823 where he discussed the principles underlying his regulations. The minute has provided historians with the clearest exposition of the ideas guiding Singapore’s early legal development. This document is a contemporary copy, transcribed in 1823, of the first page of Raffles’ ‘Minute’. Source: National Archives of Singapore

RECEPTION OF ENGLISH LAW

English law was legitimately received into Singapore through a royal charter dated 27 November 1826. Known as the Second Charter of Justice, this charter was a letters patent, or public royal command, that bore the sovereign authority of the British Crown. The Second Charter established a Court of Judicature for the Straits Settlements — comprising the Prince of Wales’ Island (Penang), Malacca and Singapore — and introduced a formally authorised and unified legal system based on English common law to replace the previous system that relied on indigenous chiefs.

The problem with the Second Charter was that there was only one Recorder (as Judges were then known) who had to travel to all three territories. This issue was resolved when a Third Charter of Justice was proclaimed on 10 August 1855. It reaffirmed the reception of English law and provided for a second Recorder to be based in Singapore, in keeping with the increase in trade and population in the colony.[4]

This document with elaborate decorative borders is the original Third Charter of Justice, issued in 1855. Together with the Second Charter of Justice (1826), it marked the formal introduction of English law into Singapore. The Third Charter also marked the first appointment of a professional judge based in Singapore. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.**Source: National Archives of Singapore

This document with elaborate decorative borders is the original Third Charter of Justice, issued in 1855. Together with the Second Charter of Justice (1826), it marked the formal introduction of English law into Singapore. The Third Charter also marked the first appointment of a professional judge based in Singapore. Courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.**Source: National Archives of Singapore

THE CROWN COLONY CONSTITUTION

A major constitutional milestone was reached in 1867 when the Straits Settlements was declared a British Crown Colony with a new constitution that granted the colony its first legislature. The Legislative Council was constitutionally delegated with “full power and authority” to establish local laws, ordinances, taxes and institutions as well as approve government appointments.

In practice, however, the British Governor wielded control over most of the colony’s affairs: he initiated legislation, had the power to veto bills and also had the deciding vote when legislature was evenly divided — his considerable powers limited only by the British Colonial Office in London.Until the 1920s the majority of the legislature members were nominated senior civil servants from the colony’s administration.

The Crown Colony constitution also paved the way for crucial judicial reforms that began the separation of the Straits Settlement’s executive and judicial arms, which had overlapped since Raffles’ time. The Governor ceased to be a judge and the reforms gave a new autonomy to the Courts in deciding matters of the law. The office of the Chief Justice also originated from these reforms: in 1868, the Recorder of Singapore was appointed as the Chief Justice of the Straits Settlements in recognition of Singapore’s strategic importance as the centre of government and commerce within the Straits Settlements.[5]

FROM COLONY TO SELF-GOVERNING STATE

When the British returned to Singapore after the Japanese Occupation (1942–45) ended, they dissolved the Straits Settlements on 1 April 1946 and made Singapore a standalone Crown Colony with its own constitution. The British also decided to gradually introduce democracy into Singapore to satisfy growing demands from the people for greater say in government. In 1948, a new constitution came into effect, which for the first time, provided for six elected seats in the legislature. This introduced democratic elections in Singapore and the first Legislative Council election was held on 20 March 1948.[6]

In April 1949, the British also permitted an election for members of the Municipal Commission (renamed the City Council in 1951), a government body in charge of municipal services such as sanitation, health, water and roads. The Commission became the first public institution to be installed with a popularly elected majority — 18 out of its 27 members were elected, taking local political participation another step towards self-governance. The remaining nine commissioners were nominated and appointed by the British colonial government.

This royal warrant was received in 1948 from the Garter King of Arms, the most senior officer of the British College of Arms, after an application by the Singapore Municipal Commission for a coat of arms. Its reception was a momentous occasion, demonstrating how Singapore’s constitutional identity at the time was firmly entrenched in traditional British ideas. Source: National Archives of Singapore.

The 1950s saw a political awakening in Singapore as well as major constitutional changes that finally brought an end to British colonial rule. The first major development was a review of the constitution by the Rendel Commission appointed in 1953 (the Rendel Constitution came into effect on 8 February 1955). Among the key changes recommended and implemented was a system of automatic registration of voters and the formation of a 32-member Legislative Assembly where, for the first time, a majority of 25 representatives were elected by the people. In the ensuing election held on 22 April 1955, the Labour Front emerged as the dominant party by winning 10 of the 17 seats it contested. Its leader David Marshall was appointed as the first Chief Minister of Singapore.

The second major development took place in 1958 when Singapore attained self-government. The Singapore Constitution Order-in-Council 1958, which replaced the 1955 Rendel Constitution, was the culmination of intense efforts by local political leaders to attain political autonomy for Singapore. In 1956, Marshall led the First All-Party Mission (with representatives from the Democratic Party, Labour Front, People’s Action Party, Progressive Party and the Singapore Alliance) to London to negotiate for self-government. When the talks broke down, Marshall resigned and his successor, Lim Yew Hock, who led the second and third All-Party Missions to London in 1957 and 1958 respectively, was able to successfully attain self-government for Singapore.

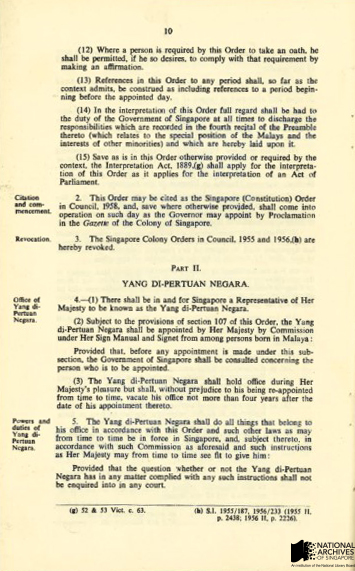

The Constitution of 1958 outlined three key objectives: it provided for a fully-elected 51-seat Legislative Assembly; replaced the post of British Governor with a locally appointed Head of State (the Yang di-Pertuan Negara); and created the office of Prime Minister. The British, however, retained control over Singapore’s defence and foreign affairs, and had a large say in its internal security.[7]

By this time the People’s Action Party (PAP) had risen to the political forefront. Following the victory of the PAP in the election held in May 1959, Lee Kuan Yew was sworn in as Singapore’s first Prime Minister on 5 June. In December that same year, Yusof bin Ishak became Singapore’s first local-born head of state, or Yang di-Pertuan Negara.

The 1958 Singapore (Constitution) Order-in-Council. These pages featured show the creation of the post of Yang Di-Pertuan Negara, the Head of State of self-governing Singapore, which would replace the British Governor. The last British Governor of Singapore, Sir William Goode, became Singapore’s first Yang Di-Pertuan Negara, to assist a smooth transition to the new constitution. Yusof bin Ishak was installed as Singapore’s first local Yang di-Pertuan Negara on 3 December 1959. On this historical date and momentous occasion, the Singapore flag was unveiled and the Majulah Singapura was launched as the national anthem. Source: National Library

MERGER AND SEPARATION

Singapore’s size and the lack of natural resources or hinterland had long underpinned the belief that it could not survive as an independent state. Merger with Malaya had been raised as early as 1955, first by David Marshall and then by Lim Yew Hock, but the Malayan Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman was not receptive to the idea. The PAP government under Lee Kuan Yew sought merger with greater urgency. Apart from the fact that the PAP had promised a merger in the 1959 election, there were other reasons why securing a hinterland was so vital towards sustaining Singapore’s economy.

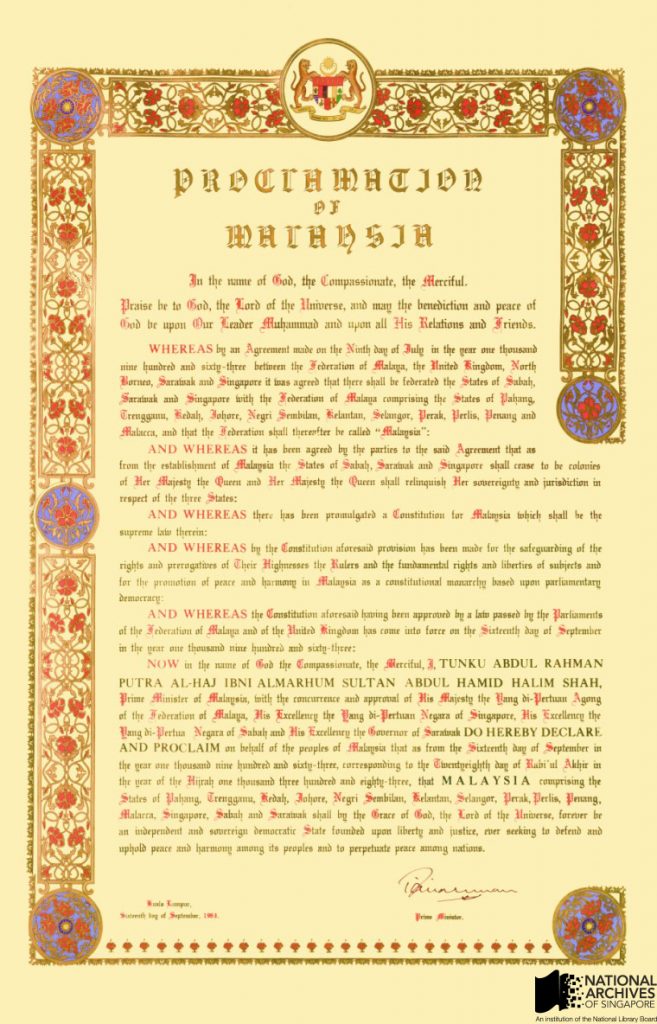

However, Lee was similarly rebuffed as the Tunku was concerned with the rise of pro-communist radicalism in Singapore and the question of how Singapore’s large Chinese population would impact Malaya’s racial balance. But in May 1961, the Tunku acknowledged the possibility of merger when speaking to foreign correspondents who were holding a meeting in Singapore. By then, the Malayan leader was convinced that it was easier to control the rising communist threat from Singapore through a merger. Merger was also made more palatable with British support for a new federation that would include the Borneo Territories — North Borneo (Sabah), Sarawak and Brunei. On 16 September 1963, the Federation of Malaysia, consisting of the former states of Malaya, Singapore, Sarawak and North Borneo (Sabah), was born, with Brunei opting out of merger. Singapore was now constitutionally independent from Britain.[8]

The Proclamation of Malaysia document declared the merger of the Federation of Malaya with the British Crown Colonies of Singapore, Sarawak and North Borneo (Sabah) into a new Federation of Malaysia. It was a formal declaration of the change of Singapore’s constitutional status to a state of Malaysia. The Malaysian version is shown here. Source: National Archives of Singapore.

Merger did not significantly change the provisions relating to the legislative and executive bodies in Singapore. Singapore was granted a new 1963 State of Singapore Constitution and retained much autonomy in the newly constituted Federation of Malaysia. Singapore’s executive and legislative branches of government retained control of the island’s day-to-day administration except in the areas of foreign affairs, defence and internal security. However, the failure to achieve economic concessions for Singapore and other political issues quickly marred relations between the Singapore government and the federal government of Malaysia. The political tussles became racially-charged, resulting in fatal riots in Singapore in July and September 1964. Separation became a necessity. The merger barely lasted 23 months.[9]

FINALLY — A SOVEREIGN REPUBLIC OF SINGAPORE

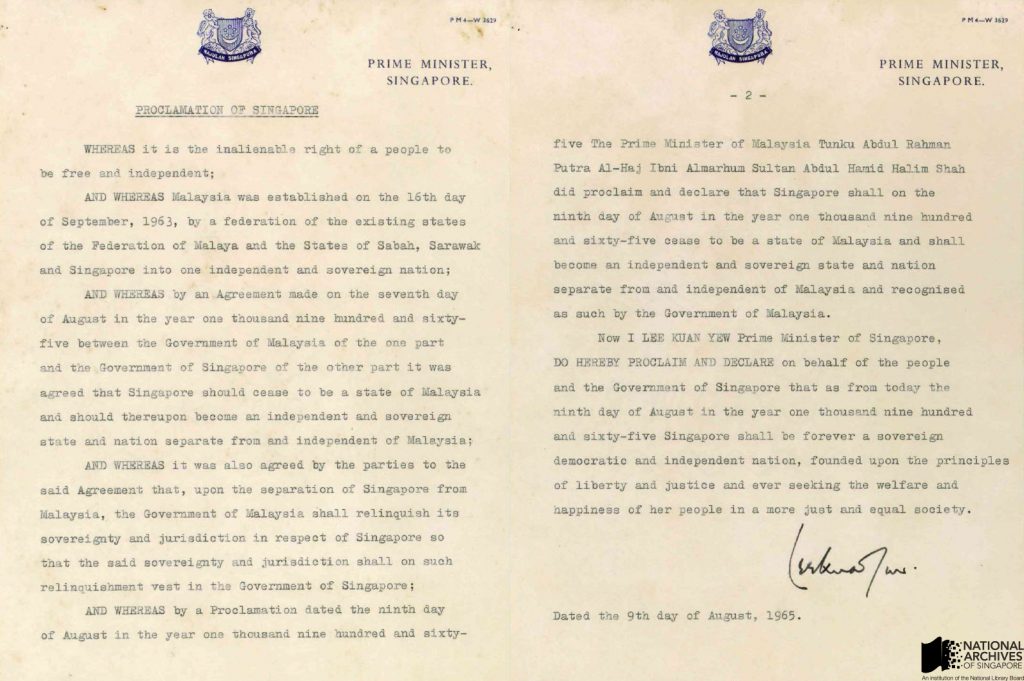

“WHEREAS it is the inalienable right of a people to be free and independent”

Proclamation of Singapore, 1965

On 9 August 1965, Singapore was proclaimed an independent and sovereign republic. The Proclamation of Singapore was drafted by Edmund W. Barker, the first Minister for Law, and signed by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. It outlined the new country’s aspirations, declaring Singapore to be forever a “sovereign, democratic and independent nation founded on the principles of liberty and justice, and ever seeking the welfare and happiness of her people in a more just and equal society”.

One of the first constitutional issues addressed in the immediate post-independence years was the need to ensure that the communal tensions that led to the riots of 1964 would never be repeated. A constitutional commission was formed under Chief Justice Wee Chong Jin to examine the constitution and introduce safeguards to protect minority rights. This led to the formation of the Presidential Council for Minority Rights.[10] As the government moved swiftly to ensure the survival of Singapore on numerous fronts, from defence to the economy, the new nation had to make do in its first decades with a composite constitution comprising the Republic of Singapore Independence Act, amendments to the 1963 State of Singapore Constitution and certain imported provisions from the Federal Constitution of Malaysia. A consolidated Constitution was issued only in 1980.

Although the basic framework of the Constitution has remained to this day, it has evolved with time to meet challenges and changing needs. Some key changes include the formation of a Presidential Council in 1970to protect against legislation that would discriminate on the grounds of race, language or religion (now known as the Presidential Council for Minority Rights); entrenchment of Singapore’s state sovereignty in 1973; the restoration of a two-thirds majority for constitutional amendments in 1979; the introduction of an elected presidency in 1991; and amendments that have created a uniquely Singaporean legislature through the introduction of the non-constituency Member of Parliament (1984), the Group Representation Constituency (1988), and the Nominated Member of Parliament (1990).

These amendments highlight how Singapore’s Constitution continues to evolve in the years to come as it strives to remain an effective guardian of the nation’s aspirations outlined in the 1965 Proclamation.

[1] Tan, K. Y. L. (2015). Constitution: Singapore Chronicles, Institute of Policy Studies, Straits Times Press, Singapore (2015), pp:110-111

[2] Tan, 2015, p. 7.

[3] Straits Settlements Records, L17: Raffles – Letters to Singapore at National Archives of Singapore; Tan, K. Y. L. (2005). A short legal and constitutional history of Singapore (pp. 29–31). In K. Y. L. Tan. (Ed.), Essays in Singapore legal history. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Academic and the Singapore Academy of Law. Call no.: RSING 349.9597 ESS

[4] Chionh, M. (2005). The development of the court system (pp. 98–104). In . Y. L. Tan. (Ed.), Essays in Singapore legal history. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Academic and the Singapore Academy of Law). Call no.: RSING 349.9597 ESS

[5] Turnbull, C. M. (1989). A history of Singapore, 1819–1988 (pp. 76–83). Singapore: Oxford University Press. Call no.: RSING 959.57 TUR-[HIS]; Chionh, 2005, pp. 104–107.

[6] Turnbull, 1989, pp.216–234.

[7] Lee K. Y. (1998). The Singapore story: Memoirs of Lee Kuan Yew (pp. 177–267). Singapore: Times Editions: Singapore Press Holdings. Call no.: RSING 959.57 LEE-[HIS]; Hickling, R. H. (1992). Origins of constitutional government (pp, 26–35). In R. H. Hickling. (Ed.), Essays in Singapore law. Petaling Jaya: Pelanduk Publications. Call no.: RSING 349.5957 HIC

[8] Kwa, C. G., Heng, D., & Tan, T. Y. (2009). Singapore, a 700-year history: From early emporium to world city (pp. 157–174). Singapore: National Archives of Singapore. Call no.: RSING 959.5703 KWA-[HIS]; Turnbull, 1989, pp.251–285.

[9] Lee, 1998, pp. 540–663; Turnbull, 1989, pp. 251–285.

[10] Tan, 2005, pp. 48–54.